Subscribe to Blog via Email

Join 329 other subscribersMarch 2026 M T W T F S S 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 22 23 24 25 26 27 28 29 30 31

Kaliarda XXVIII: Sarantakos

Nikos Sarantakos has just published on his blog a report on Spatholouro’s finds in his blog comments of early attestation of Kaliarda, as already reported here. My thanks to him for disseminating Spatholouro’s findings more widely, as they deserve.

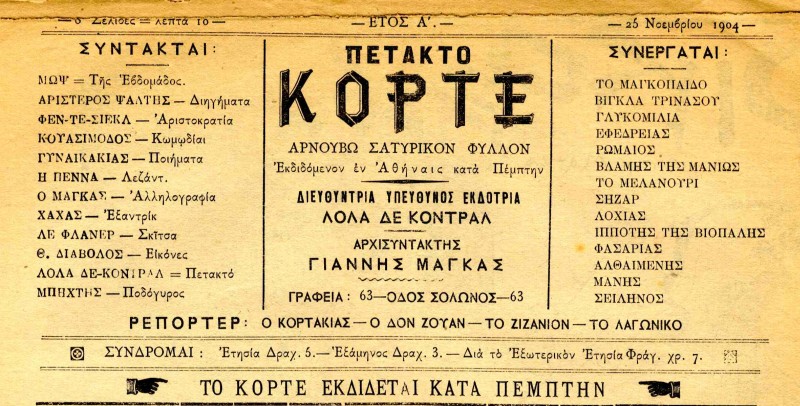

There’s not a lot of new information in the article, but he does mention that Manganareas’ journal Πεταχτό Κόρτε “Fleeting Flirt”,

despite its editor’s activist credentials, was one of the risque magazines of the time, with half-naked women drawn on the front cover, with cartoons with innuendo-laced captions showing ladies in negliges, with poems and witticisms full of double entendres, often italicised (e.g. “every female reader should give it to her friend—the magazine, that is.”) […] As you can see on the front cover above, the magazine shows dozens of pseudonyms of contributes, but I would not be surprised if the entire content was written by Manganaras with 2 or 3 collaborators.

Sarantakos also raises a criticism of Petropoulos’ work that is worth discussing: the lengthly witticisms in the dictionary don’t seem to be conventionalised parts of a normal cant vocabulary, but one-off opportunistic inventions, which his consultants happened to come up with:

But users of cants don’t use it so much to communicate, as to not be understood by outsiders. They don’t need to devise words for all aspects of life, because the mainstream language is enough for that. They need 100–200 basic words for their immediate interests (money, client, beautiful, ugly, small, big.)

The sense I get every time I leaf through Petropoulos’ Kaliarda is that many, if not most of those words were made up by a small group for fun, building on the existing model of Kaliarda vocabulary. I open up Petropoulos at random at <R>, and read these entries:

- rena: queen [French reine]

- renovlastos: “queen sprout”: heir to the throne

- renoɣlastra: “queen flowerpot”: palace

- renokaθiki: “queen chamberpot”: crown

- renokatsikaðero: “queen goatville man (= hillbilly)”: evzone (royal guard, in traditional rural garb)

- renos: king

- renoskamnu: “queen stool”: throne

- renotekno: “queen child”: prince

The compounds are very witty and inventive, and I bet the people who made them up had a lot of fun doing so; but I would be surprised if they were ever widespread among Kaliarda speakers. I fear that Petropoulos, yielding to the passion of the collector, bolstered his collection by recording the opportunistic formations of a small group.

I agree with Sarantakos that it’s unlikely that these witticisms were conventionalised—that “queen chamberpot” was the regular word for “crown”, used more than mainstream stema or korona (whenever crowns did come up in conversation). I disagree that they were out of bounds for being recorded.

Kaliarda at the beginning may well have been as limited as Dortika, when it really was being used as a secrecy language, by sex workers and gays. The minimal records we have of older Kaliarda concur: they don’t have the compounds, the jokes, and the allusions that Petropoulos recorded. (Of course, they were quite basic vocabularies, so there’d be no room for them anyway.)

But Petropoulos says that wit is a major component of speaking Kaliarda; in fact, wit is also emphasised in accounts of the much more parsimonious Lubunca, and were clearly also at work in Polari. Even in 1928, Hatzidakis says much the same about Kaliarda—that the experience of hearing any word of it is unforgettable; and I find it hard to believe that it was unforgettable merely for using a couple of Romani words in a mincing accent. Even if the coinage “queen chamberpot” was not conventionalised for “crown”, and was the invention of one particular Kaliarda speaker, I suspect that kind of coinage happened among Kaliarda speakers all the time.

And beyond that, the linguistic patterns of the coinages are revealing of how the language work. dzasberdepurotsarðo is rechercé for “National Benefaction”, and “house of an old man throwing away his money” is clearly one-off. But I doubt this was the only time dzas-berde was used to refer dismissively to philanthropy; and the variant clearly permitted such four-part compounds to be formed and understood—something not without precedent in Greek, both literary and colloquial, but in a much more schematic garb than we’re used to from Greek.

I’m going to be offline for a couple of weeks. When I get back, I’ll be posting glossed highlights of the Kaliarda vocabulary, and drawing this series to a close.

in u.s. queer/trans language, the point of the ease of making one-off compounds is partly the pleasure of invention, but also partly to allow meanings to remain obscure even when one variation does become cemented into a permanent word. once “mary blue-dress” (and its variations) means “cop” too transparently, it’s off to the races again to find another phrase… “opportunistic formations” are what any researcher would get at any specific moment, because making them is the structure – very few independent nouns, tons of kennings, if you will.

the same seems likely to be true in lubinistika/kaliarda. which is basically to say that i agree with your take on sarantakos’ critique.

but i wouldn’t minimize the importance of a “mincing accent” either. no one in my circles would mistake the inflection/stress/vowel-feature variations that make “girl” mean “trans woman”, “sex worker”, “cis woman”, “young woman (cis or trans)”. and few of those meanings would be transparent to a straight eavesdropper unless they were specifically ‘wise’ – and fewer are than think they are, these days.

[…] Kaliarda XXVIII: Sarantakos […]

Every year, one of the great dictionary publishers (Langenscheidt) has someone walk into a school in Germany and record candidates for the Youth Word of the Year. Every year, the kids make stuff up that nobody has used before or since, and Langenscheidt dutifully falls for it. By now I expect they’re in on the joke, but who knows.