Subscribe to Blog via Email

Join 329 other subscribersFebruary 2026 M T W T F S S 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 22 23 24 25 26 27 28

The phonology of “Sitia”

No hyperlinks for this post, as my internet time is rationed while I’m on holidays.

Sitia, which is my hometown in Crete, does not figure prominently in history. The guidebooks say that in antiquity it was Eteia, and gave birth to Myson, one of the Seven Sages of Antiquity. The only Sage out of the set anyone’s heard of is Solon, and the Seven Sages were some sort of mythic convenience anyway, so that doesn’t count.

Sitia does turn up in the Middle Ages, with its S. It turns up in the Notitiae Episcopatum, the lists of bishoprics of the Empire. The lists went through a dozen generations, and were increasing garbled and fictionalised, as more and more of the sees they listed had not seen a Christian clergyman in centuries. The lists lived on in the West, and were used to generate the titular sees of the Catholic church: a way of granting someone a bishop’s title without a bishop’s responsibilities (unless they were minded to go over and convert Nisibis back to the True Faith).

Because the Catholic lists are available on the Intertubes, and the Orthodox lists are on dead tree I don’t have, the Catholic lists have often come to my rescue when I was adding placenames to the TLG lemmatiser. Particularly as the Catholic lists include the Latin nominative, while the Greek lists stop at the morphologically ambiguous genitive. So the Latin gave me as good a guess as any as to the gender of the towns listed.

Sitia turns out in two Notitiae, as Σιτία and Σιτεία. I don’t have dates on the Notitiae, since I don’t have the dead tree full text.

There are other mentions of Sitia here and there, some Byzantine, some Venetian, few Ottoman (the town was abandoned from the Ottoman conquest until around 1870). But the mention I’m going to dwell on is from around 1460; and I’m going to dwell on it because it has an oddity of historical phonology.

First, the phonology that the oddity perturbs. In Cretan, /t/ is lenited to /θ/ before [j]. So the plural of [ˈmati] in Standard Greek is [ˈmatja] “eyes” (from Ancient ὀμμάτια); in Crete it’s [ˈmaθja]. “Fire” is [foˈtja] in Standard Greek, and [foˈθja] in Crete. The singular of “eye” is still [ˈmati] thoughː the rule only applies when /i/ is not a syllable—that is, when it precedes another vowel. The rule is general enough for Cretan songsmiths to have taken advantage ofː

Δεν εκυνήγα λαγούς κ’ ελάφια

μόν’ εκυνήγα δυο μαύρα μάθια.ðen etʃiniɣa laɣus tʃ elafja

mon etʃiniɣa ðjo mavra maθjaHe would not hunt for hares and deer;

he’d rather hunt for two brown eyes.

This particular song has travelled far; it’s travelled as far as Mani, and from there to Corsica, without the phonetic rule that /t/ goes to /θ/. So when Maniats sing it, not only does [elafja] not fully rhyme with [maθja], it doesn’t even partially rhyme with [matja].

The song has travelled even further than Corsica: it’s made it all the way to the eastern tip of Crete, Sitia, which is the only part of the island that the rule does not apply. I heard the song several times while I lived in Sitia; I never heard the song rhyme, because the singers would sing it the way they spoke the dialect, and not the way the other seven eighths of the island did.

The name of the town, like I said, is Sitia, [si.ˈti.a]. The name has [i] as a separate syllable from the following [a], and that should tell you it is not a colloquial form: the vernacular rule is that [i] before a vowel goes to [j], and if it doesn’t, the form isn’t vernacular. That’s why the word for fire is [foˈtja], though it used to be [foˈti.a]. That’s why άδεια is pronounced two ways, without the spelling telling you which: [ˈa.ðja] for the colloquial adjective “empty”, [ˈa.ði.a] for the learnèd noun “leave, day off” (which is, literally, an empty day). The word for Turkey is now Τουρκία [tur.ˈki.a]; but folksong and previous centuries knew the Ottoman Empire as [tur.ˈkja] > [tur.ˈca], Τουρκιά.

Which means the town should have ended up called [siˈtja], and anyone from outside the town should have ended up calling it [siˈθja], just as they say [foˈθja].

That’s not what’s happened. The Renaissance poet Vincenzo Cornaro was from Sitia: the most renowned son of the city until contemporary Greek pop sensation Giorgos Mazonakis. And in the epilogue to his great romance Erotokritos, he introduces himself, and his home town:

Βιτσέντζος είναι ο ποιητής, και στη γενιά Κορνάρος,

που να βρεθεί ακριμάτιστος όντε τον πάρει ο Χάρος.

Στη Στείαν εγεννήθηκε, στη Στείαν ενεθράφη,

εκεί ‘κανε κι εκόπιασε ετούτα που σας γράφει.The poet is Vincent, of Cornaro stock:

may he be sinless when he’s Death’s to take.

In S’tia was he born, in S’tia bred;

there did he write and labour what you’ve read.

So the town did not end up as [siˈtja], but as [ˈsti.a]. Cornaro’s quite careful about hiatus in his verse: vernacular verse avoids two consecutive vowels in separate syllables, just as the vernacular phonology did. In fact, he made a point of nativising Classical loanwords like περικεφαλαία [pe.ri.ke.fa.ˈle.a] “helmet” to the more vernacular-sounding περικεφαλιά [pe.ri.ke.fa.ˈʎa]. So if Cornaro is writing [ˈsti.a] (and we know the syllable count because of the metre), then that’s what the place was called in the vernacular.

As indeed it is called by the locals to this day: the town is Στεία, the adjective is Στειακός. The surrounding villages preferred to call it Το Λιμάνι, “the harbour”, because it’s where their produce ended up. And the local name S’tia still has that non-vernacular hiatus in it. It isn’t supposed to: the Ancient word for hearth, ἑστία [hestía], has ended up in other Modern dialects as their word for fire, στιά [stja], and phonologically that should be the same as S’tia: the reduction to one syllable should not have made a difference.

So the town name is more archaic than it’s supposed be. But that’s not in fact the conundrum I’m leading to. The conundrum I’m leading to is how the town gets named by Michael Apostolius.

You will occasionally, in accounts of Greek lexicography, come across plans to span all of Ancient Greek literature from Homer to Apostolius. Michael Apostolius (or Apostolis, the more vernacular form he used himself), was one of the many scholars who fled Constantinople after its Fall to the Ottomans. Greek was written before Michael Apostolius, and Greek was written after Michael Apostolius; but even though much of that Greek strove for compatibility with the Ancient norms, it has usually been beneath the notice of Classicists.

Apostolius marks an endpoint for Classicists, not because he wrote any Greek himself that they care about, but because he was the last Byzantine editor of a text they care about. There are three major collections of Ancient Greek proverbs: Diogenian’s and Zenobius’ from Roman times, and Apostolius’, who fills in some of their gaps. So lexicographers need to go through Apostolius’ proverbs, just as they need to go through the scholia to Ancient texts—the latest of which were written not long before Apostolius: to get as complete a picture of antiquity as can be recovered from the Byzantines.

So there’s one text by Apostolius that Classicists care about. There’s another text that less people care about: a collection of his correspondence. The collection was edited in 1888 by a scholar called Hippolyte Noiret, who died in his twenties before he could see it in print. I sighted a copy at the ANU library when I was there, looking somewhat forlorn; but it has also been added to the TLG.

I haven’t got around to reading the preface to Noiret’s edition entirely, but I was amused to read Noiret found Apostolius to be childish, both in his energy and his impetuousness. Whereas other Greek scholars ended up in Italy, taking up jobs at universities or printing presses, Apostolius ended up in a lower-rent version of Italy: Crete, which had been a Venetian colony the past two hundred years. Apostolius was always struggling to make ends meet as a scholar for hire, but he did travel widely through the island, and report back to his many correspondents. And one of the places he mentions is Sithia.

Seeing Σιθία in print took me by surprise. Was this supposed to be Σητεία? Noiret doesn’t address the question, and I wouldn’t have expected an answer from Google; but Google does now index old journals, even if the publisher is only making the back issues available through institutional subscriptions; and a snippet of a Byzantinische Zeitschrift article from the 1950s looks like confirming that yes, Σιθία is the town in the North-East of Crete.

There’s further confirmation from one of the letters where Sithia is brought up: the person carrying the letter was seeking to be appointed bishop of Sithia, and Apostolius trusts that his correspondent will help the letter-carrier in his efforts:

XCII: To the admirable Bessarion.

Since I am in receipt, wisest of cardinals, I have reported to you in the last writing, which three pious peasant priests have brought, that without your generous and gratifying contribution, namely the benefaction of twenty gold coins, I have no other income from any other source—as I am currently feeding five people, and now moreover another newborn child by the name of Aristobulus, whose father I have been called literally; and I now have an heir not in money, but in family. And if I ever happen to broach the topic of the scarceness of children (?) , I also owe some rent; the priests are my witnesses as to whether I speak the truth. Therefore, bearing in mind how I will turn out in my old age, and whence I will have resources to marry off my dearest children, I pray to you, prudent and generous, and would exact from you advice as to what I should do: whether I should come there and serve you with the others, or whether I should allow myself the solution of inquiring about Germany and England, and the surrounding districts as well, in the manner about which I shall come and kneel before your lordship and report to you.

But so much for that; and as I am friend to God, so may I be as well to you, my lord. Now, the one bearing this letter is a Cretan from good Cretan parents, who has lived saintly and justly. And being thus worthy of priesthood, he has kept company as if born and reared, first with a certain holy bishop of the Gortynians, then after a short time with the bishop of Cydonia as well—who was your attendant and who has also followed you in Venice and elsewhere. Being such and born of such, it is necessary—for you and many others, and through myself—that he become bishop of Sithia. He is who all Sithians want, and seek as their bishop because of the impeccability of his life, and because he is their family and familiar to them. For he too is Sithian, born and reared and living there. If you should help this man (and I hope you will help him promptly, emulating your innate generosity in this matter too), then you shall do what is pleasing to God, and natural to your forebears, aiding the poor and the good; and what is hoped for and dear to the Sithians. And you shall show me too to be good, a pauper helping a pauper, submitting myself to reciprocity.

If Sithia is a town in Crete big enough to have a bishop, and Sitia was already known from the Notititae to have a bishop, that does narrow things down a lot. It narrows the timeframe too: Sitia no longer has its own bishop, and is under the authority of Hieraptyna (now Ierapetra, “Holy Rock”, through folk etymology, and in the local pronunciation [ʝeˈrapetra]). That may be because Sitia was depopulated for a couple of centuries; dunno.

And if the letter was written in the 1460s, that’s not a Greek Orthodox bishop’s position he’s talking about either. The lobbying needs to happen in Italy, because Venetian Crete had Catholic bishops; the Orthodox islanders had to look to Modon (Methoni) for their spiritual guidance. Apostolius was Catholic himself, and several of his letters are about how to combat the schismatic Orthodox on their turf. The addressee, Cardinal Bessarion, was himself Catholic (which tends to be a prerequisite for being a Cardinal), and a good target for lobbying; he too was a convert from Orthodoxy, and one of the more prominent Greek intellectuals of his day.

But I’m still stuck on what Apostolius calls the place. [siˈθia] is not [ˈsti.a]. The /i/ hasn’t gone to [j], so the lenition doesn’t make sense by Modern Cretan standards. Moreover, as Chatzidakis already wrote a century back, there’s no evidence for the lenition from Renaissance literature, so the change must date from after 1669 anyway. When exactly I don’t happen to know, because the readiest evidence for that would lie in Ottoman archives, and Greeks until fairly recently liked to pretend the Ottomans had no archives. (Turci sunt, non leguntur.) But the change can’t date from the 1460s, and even if it did, it wouldn’t be as [siˈθia].

There’s another placename in Apostolius which probably confirms the absence of the sound change, but has problems of its own. The three western prefectures of Crete are named after their major cities: Hania, Rethymnon, Iraklion (formerly Kastro, “The Fortress”, and Candia before that). Sitia never made it to major anything-at-all status; so its prefecture is Lasithi, named after the mountain plateau to its west. Lasithi is also mentioned by Apostolius, as Lasition. That would be consistent with /t/ > [θ] / _i, and the plateau is far enough from Sitia for the change to be allowed there.

The problem this time is, the /i/ is not [j], because the -on ending had long been deleted in the vernacular. So the sound change can’t have happened: a learnèd Lasition corresponds to a vernacular Lasiti, not a *Lasitjo that would have gone to *Lasithjo. (Just as ὀμμάτιον /ommátion/ “eye” went to [mati(n)], not [matjo].)

So in Apostolius, we have a th in Sitia and a t in Lasithi, neither of which make sense by how the modern dialect works. The form may not just be Apostolius’ imaginary friend either: you will on occasion see the spelling Sethia in Venetian documents, although I’d assumed it was just the random insertion of h‘s that transliterations of Greek are susceptible to.

So how can we explain Sithia? I don’t know that we can; maybe it is just one of those things, a local variant without rhyme or reason. Which is the kind of defeat an historical linguist is never meant to admit to. There is a possibility that the vernacular form was actually Sithia all along; if Sithia was shortened to S’thia, S’thia would have to become Cornaro’s S’tia by vernacular phonology, which does not tolerate the /sθ/ cluster either. But the Notitiae have Sitia from earlier on, so I’m not convinced that’s what happened.

There’s one more feature of Apostolius’ letter which comes as a surprise. Ethnonyms, the names of people derived from where they’ve come from, have a multiplicity of suffixes to choose from in Greek. There’s a similar diversity in English (which is not completely unrelated): New Yorker but Washingtonian, Muscovite but Milanese. For the Byzantines, this multiplicity meant abundant confusion about which was the right suffix to use when writing Classical Greek. For that reason, Stephen of Byzantium wrote the Ethnica, a dictionary of ethnonyms; and because it is chock full of towns and ethnonyms never heard of before or since, it’s one of the texts the TLG lemmatiser has the most difficulty dealing with.

For Modern Greek, that multiplicity means an excuse for parochialism: every village picks its own suffix to names its people. Zakros has Zakrites; 20 km up the mountain, Ziros has Ziriotes. And the people of S’tia are S’tiaki, Στειακοί.

In Apostolius’ letter, they aren’t S’tiaki though; they’re Σιθιανοί, Sithiani.

This came to me as even more of a shock than the [θ]. Surely the S’tiaki have always been S’tiaki; surely this proves that Apostolius was making ethnonyms up.

Of course it doesn’t, though. Ethnonyms do change in time, and assuming the vernacular of 1460 is the same as that of 2010 is a mistake students of Early Modern Greek are all too prone to. Cypriot is the ethnonym used in English because Κυπριώτης [kipriotis] was the ethnonym that used to be used in Greek. In fact it’s the form used in Erotokritos. But Standard Greek only knows the form Κύπριος [ciprios], and Cypriot itself uses Τζυπραίος [dʒipreos].

And after all, there was a time before S’tiaki and Sithiani, when inhabitants of Sitia were called something different again. When Diogenes Laertes wrote about Myson of Chen, he brought up the conundrum of why he was also termed Ἠτεῖος [ɛːteîos]. Diogenes speculates that maybe one of his parents was from Eteia instead, “for Eteia is a city in Crete”.

Assuming Eteia is Sithia is Sitia; and the assumptions in this line of work are always more tenuous than you might think. (The assumption that Eteia is Sitia is why the town is now spelled with an eta, though: Σητεία.) And I still don’t know where that [θ] in the name came from. Or that initial [s] for that matter (although the metanalysis of /eis ɛːteían/ “to Eteia” to /eis sɛːteían/ is as good a cause as any).

More on Lazaros Belleli

Readers may remember I posted a couple of posts earlier in the year on Lazarus Belléli, and his bareknuckled fight with Dirk Hesseling over publishing the Judaeo-Greek Torah. I relied on googleable sources to get background on Belleli, about whom I’d heard nothing since his fight with Hesseling; thanks to the online 1901-1906 Jewish Encyclopaedia, I found that he represented the Jewish community in the trials following the 1891 Corfu pogrom (see the contemporary Australian newspaper reports); and that he ended up in England, unable to get a job in Greek academia.

The 1891 Pogrom was the subject of a post on the Magnificent Nikos Sarantakos’ blog, and I took the opportuntity of asking if anyone knew something more about Belleli. My thanks to Theodoros “Dr Moshe” Moysiadis, Maria, and Abravanel for their responses. Because I seek to make Greek linguistics more googleable in English, here’s a little more on Belleli.

(As always in our corrupt age, I update a hundred-year old online reference with other online references, instead of hitting the library. I know, I know…)

- From Dr Moshe, translating:

It is true that Lazaros Belleli spent several years in London a the beginning of the 20th century. He was an ardent demoticist and regularly contributed to Noumas [Numa] magazine. [Greek Wikipedia; Full run online at Cyprus University]. A sample of his language, which was characteristic of all close followers of Psichari, can be seen here (in the article Ένας Σπουδαίος Δημοτικιστής, “A Great Demoticist”). He was intensely occupied with Modern Greek literature, and among others, he brought to public notice Kalvos’ Italian tragedy Le Danaidi [as Andrea Calbo].

But we should note that Lazaros Belleli was finally apppointed in 1928 [and again in 1932] as visiting professor in a subsidiary chair (επικουρική έδρα) in Thessalonica University, specialising in “History and literature of Jews and other Semitic peoples” (as is mentioned in the 1932 University Calendar, p. 7, [on the same page as Manolis Triantafyllidis])

- Belleli’s article is on a Timotheos Kyriakopoulos, who published a Christian catechetical work in the vernacular in 1759.

- As Abravanel pointed out, the establishment of a Jewish Studies programme at Thessalonica raised the fury of the Venizelists against Prime Minister Papanastasiou. (The linked history claims that “Papanastasiou’s efforts failed, and the University of Thessalonica never opened its doors to Jews”. Papanastasiou had envisaged a Jewish Theological School, but in the end Jewish Studies got one chair in the Languages programme.)

- The proviso Dr Moshe raises about Psichari-style Demotic is often needed because Psichari’s Demotic is not Modern Demotic. Psichari was trying to get Abstand for the language he was advocating as a new literary norm; this made it folksier-sounding than the contemporary language, which has compromised appreciably with Puristic. The feature that stands out immediately in the issue is the use of final /e/ added to final /n/, which in the modern language is restricted to song lyrics. (Και δίχως να τ’ ακούσω από τον ίδιονε…)

- Incidentally, I had Greeked Belleli as Μπελλέλι, but he himself Greeked it as Βελέλης [Velelis], to be more compatible with Ancient Greek phonology (and thus, look less alien). That was quite commonplace Hellenisation at the time (the prime minister at the time was Δεληγιάννης, Deligiannis, from Turkish deli “crazy”) And by not Hellenising his surname as much as he hellenised it, I have done him a disservice.

So did getting a lectureship in Jewish Lit at 66 years of age, in the most Jewish city of Greece (at the time) count as a vindication? Possibly, given that he tried—and failed—to get the Chair of Hebrew at Athens U. Then again, maybe not, given what Belleli was up to in London in 1918.

Thanks to commenter Maria, I refer you to Richard Clogg. 1986. Arnold Toynbee and the Koraes Chair. London: Frank Cass. (Middle Eastern Studies 21.4). The book is about the politicking in establishing the Chair in Modern Greek and Byzantine History at King’s College London, which was held by Arnold Toynbee, before he became big as a comparative historian (and antagonised his Greek funders by criticising the Greek occupation of Turkey). Belleli has a bit part in the politicking; he was one of the candidates.

Clogg portrays Belleli (pp. 30–31) as a nutter (“the most eccentric applicant was Dr Lazaros Belleli”), and the paperwork he lodged to support his application (“an extraordinary 32-page typewritten letter”) probably justifies the judgement. His glee at maneuvering to prevent Dirk Hesseling receiving the Zographos linguistics prize is, to say the least, unseemly.

But the phrase he introduces himself with is not odd at all, though Clogg fails to pick up on the subtletly: “Describing himself, somewhat confusingly, as ‘being a Greek by birth and Italian by family’…” Belleli’s native language was Italian (or Italkian), being a Corfiote Jew, and he had his doctorate from Florence; especially after 1891, he would not have been eager to present himself as Just Greek, even if he was applying for the Greek position. As it turned out, that wouldn’t have helped anyway: the position was earmarked for an Englishman.

And that’s as much as I can find on Belleli.

History of Australian English

This post is not about Greek, although there are parallels with a couple of phases of the history of Greek.

I picked up Speaking Our Language: The Story of Australian English, while in Sydney. It’s a history of Australian English for the general audience, written by Bruce Moore, a lexicographer at the Australian National Dictionary Centre. It’s a bit more laundry-list lexicon-heavy than other linguists might do, but it’s a very entertaining read, and has some interesting theories.

Moore puts forward the formation of an Australian English as a dialect koine in Sydney, within two generations of settlement, and then diffusing out of there rapidly. (There were no administrative barriers between provinces like in the States, hence the astonishing regional homogeneity of Australian English.) This is common sense, and reflects other koineisations (and creolisations). New Zealand has done a better job than Australians of tracking their linguistic history, and the accent data from the first generation of native born New Zealanders, available through recordings done in the 1940s, was critical to proving that contention. Their accents were not yet fully levelled, and even children growing up in the same small town had slightly different accents. It was only the second generation of native born colonists who had a local norm to peer pressure themselves into, and knock out any deviation.

In line with that, it was only after the second generation that dialect loans from Northern English and Scots into Australian English were possible. In the first generation, such words were still sensed as outliers from the emerging Southern-England based koine, and ruled out.

It was also good to see a serious treatment of how attitudes towards Australian English developed in line with attitudes to Australian identity. The rush of Australian republicanism in the 1880s accompanied the first scholarly interest in the version of English spoken here. The long sleep of my country’s identity, as Federation transformed it into an Imperial lickspittle, also saw noone bother to look at Australian English between 1900 and 1965.

Australian English was traditionally stratified by class, divided into Cultivated, General, and Broad. Lawyers on 70s TV dramas all spoke Cultivated—which is pretty close to RP English. With the resurgence of Australian nationalism in the 80s, it is now unsafe to speak Cultivated Australian in public. Anything that drives a stake into the heart of Lickspittle Australia is OK in my book. (Or rather, *that* tradition of Lickspittle Australia. We are obeisant to other masters now. And it’s not primarily the US any more either.)

General and Broad are still around, with Broad the Australian you’ll hear from stereotypes on TV, and politicians in parliament (for similar reasons): “mɨstə spɜɪkʰə, ðɪ ɔnərəbl mɛmbə fə bæŋstæən ɪz ə bɐm”. Moore reports Broad is on the decline, which is a bit of a surprise.

Moore’s guess about the origin of Broad Australian is intriguing, though on flimsy evidence. What little longitudinal data we have from country speakers may suggest Broad Australian is newer than General Australian; his guess is that Broad arose in the World War I trenches, as a reaction against the British English the diggers heard around them. It was certainly also a reaction against the Cultivated Australian that started to be promulgated in the 1890s.

The funny thing is, commenters until the 1890s kept saying how Pure the Australian accent is. By that, they meant it didn’t sound like any English accent in particular. It also didn’t sound like Received Pronunciation, but that adverse comparison couldn’t be made until RP itself became mainstream in British education, just before then.

Moore predicts Broad Australian will vanish because the Cultivated Australian it reacted against has perished, and the ideological dispute between Lickspittle and Patriotic Australia has settled down. (You may have discerned I have a slight bias in this matter.) I think Moore is underestimating the fissures in Australian society. But he rightly points out that now that the Australian linguistic situation has settled down somewhat, the emergence of a second generation immigrant koine (“wogspeak”), which defines itself against Anglo norms, can be seen more clearly. (The link is to an interview Simon Palomares did in 2004, and Moore cites it too: it’s quite insightful. Some readers may recall Palomares as the Spaniolo in Acropolis Now.)

That’s a different fissure though. In fact, even that fissure may be starting to play itself out, as the Mediterranean immigrants’ children assimilate, and a new generation of immigrants take their place.

Oh, and that’s Acropolis Now as in the ’90s sitcom about Mediterranean-Australians, not as in the radio sitcom set in Ancient Greece by renowned Punctuation Nutjob Lynne Truss. (Obligatory Approving Link to the Great Smackdown by Louis Menand.) Here’s hoping she does radio comedy more effectively than she does pedantry…

Andronikos Noukios, aka Nicander of Corcyra

There won’t be much from me here this month, as I’ve been on the road and still am. However, a chance discovery I made at the ANU Library leads to another superficial post on Greek diglossia; with me away from my books, that’s as much as I can do.

In the 1540s, Andronico Nunzio from Kerkyra (Corfu) was working as a copy editor in Venice, preparing Greek texts for publication. He was responsible for editing a couple of missals (typika). He also copied a manuscript of Porphyry. That’s the kind of low-level scribal work you’d expect of a Renaissance humanist. As you’d also expect of a Renaissance humanist, his surname was Hellenised into something more reputable-sounding: after some hesitation, he ended up as Andronikos Noukios, Andronicus Nucius.

Andronicus also wrote three books. One was a translation from Italian that I can’t find anything about online, and I don’t have the book I read this from by my side.

The second was an account of his travels to Northern Europe, in Ancient Greek. That was the chance find at ANU: the 1962 edition of his Voyages. This is the kind of text I love, as you know from my adventures with Laonicus Chalcocondyles: lots of references to Western Europe through the ill-fitting garb of Ancient Greek.

Someone writing a travel account in the 1540s in Ancient Greek is no surprise: it was the learnèd language of the time, and writing in Modern Greek was simply not a serious option. The Voyages have been translated in French in 2003 (see also Google Books); and the publishers’ blurb is taken with the antick garb of the language—

Nourri de culture classique, Nicandre rédige en grec (ancien !) ses observations des lieux et des gens. Cambrai dépeinte comme par Strabon, ou Paris décrite comme par Plutarque, ça ne manque ni d’étrangeté ni d’allure !

Brought up in Classical culture, Nicander writes up in Greek (Ancient Greek!) his observations of places and peoples. Cambray, depicted as if by Strabo; or Paris, described as if by Plutarch: something not lacking in either strangeness or allure!

But that is misguidedly exoticising what was a quite natural thing for a Renaissance Greek scholar to do. Noukios wasn’t writing in Ancient Greek to be cute: he was writing in Ancient Greek because that’s what scholars did.

In writing his account in Herodotan Greek, Noukios amped up his self-hellenisation all the way up to 11: he switched Andronicus (a good Byzantine name) to Nicander, just as Nicholas Chalcocondyles styled himself as Laonicus. The book is still inscribed as Nicander Nucius’, but the 1962 editor de Foucault has titled it as being by “Nicander of Corcyra” (= of Corfu)—presumably with plenty of motivation by Noukios himself. That has misled at least one antiquarian bookseller to conflate him with the slightly more famous Nicander of Colophon, 2nd century BC.

Beyond the 1962 edition and the 2003 French translation, the section of the Voyages dealing with Nucius’ stay in Britain was translated in English in 1841, and is available in full online courtesy of archive.org and the wonderful people of the University of Toronto.

(The book reviews for the French translation have pointed out that this is the reverse of the usual Orientalist voyage: an Oriental exploring the Occidentals. They did not say it that crudely, but I did still growl “screw you, Beef Eaters”. Here’s one more review.)

The third text Andronicus wrote (under the much abbreviated signature ΑΝ. ΝΟΥ. ΚΕΡΚ.) was the first Modern Greek rendering of Aesop.

The text has been published in a modern edition in 1993, but it had stayed in print for three centuries from 1543, in increasingly decrepit state, as a popular chapbook. The text’s modern editor, Georgios Parasoglou (papyrologist at Aristotle U, Thessalonica), notes that the translation is pretty poor—it’s a rush job, done to order. The Venetian publisher knew they had a market for fairy tales in Modern Greek, and grabbed the first copyeditor they had to hand for their churchbooks. Nucius for his part wasn’t going to Nicander himself up for such a vulgar undertaking.

There is a surprise to Modern Greek readers here. Parasoglou feels the need to point out that no, it’s not a surprise at all, Andronicus was neither the first nor the last scholar to write in both Ancient and Modern Greek. Indeed he was not. Cardinal Bessarion was a scholar’s scholar; but his letters home were pretty close to vernacular. Hans-Georg Beck is renowned for pointing out that the first writers of Modern Greek, in the 12th and 14th centuries, must have been literate and cultured in Ancient Greek, and studies of early vernacular Byzantine novels are highlighting that they belong to the same literary tradition as the novels written in Ancient Greek a century before.

This all should be obvious: literate people knew both Ancient and Modern Greek, and wrote in both. But to a contemporary Greek, this does not compute. It does not compute that the current English Wikipedia page on Byzantine novels does not even mention the shift in language between the 12th and 14th century. It does not compute that the Classical Nicander and the Vernacular Andronikos could be the same person. Or, to use an example thanks to Notis Toufexis, it does not compute that Theodosius Zygomalas could complain (in Ancient Greek) how horribly degraded the Modern language had become—and then turn around and do a quite creditable translation into Modern Greek of the Stephanites and Ichnilates (ultimately from the Panchatantra).

It does not compute, because of the peculiar poison of Modern Greek diglossia. Noukios could write vernacular for hire, Zygomalas may even have written vernacular for fun, but still keep to Ancient Greek as their working languages. But in Modern Greece, you had to choose. In the 20th century, you were either a Demoticist or a Purist—a Longhair or an Ancestor-Worshipper. In Athens in the 1880s, you didn’t even have that much choice—which is why Roidis had to deride Puristic in Puristic, and why the late 19th century pioneers of Demotic prose all lived in the diaspora.

And that binary thinking makes it comes as a surprise that Modern Greek was first written by men literate in Ancient Greek, and that the rhetoric in Libistros and Rhodamne has much in common with the rhetoric of Hysmine and Hysminias, even though they don’t share datives and infinitives. The Modern battle between the languages blinds us to the obvious truth that, in earlier times, you didn’t have to choose.

Which reminds me of another binarity of Modern choice that didn’t used to apply. The Balkan Sprachbund, with the grammatical convergence of the languages spoken throughout the area, could only have happened if you had lots of bilinguals in the Balkans—indeed, trilinguals and quadrilinguals. After the Balkan Wars and population exchanges, and the State policy of discouraging minority languages, it’s hard for a Greek in particular to picture what a plurilingual Balkans might have looked like. But the linguistic evidence for it is clear.

Similarly, the literal equivalence of oodles of Turkish and Greek proverbs gave rise to a famous paper, which got cited a lot at me when I was an undergrad. (Tannen, D. & Oztek, P.C. 1977. Health To Our Mouths: Formulaic Expressions in Turkish and Greek. Berkeley Linguistics Society 3. 516-534.) I was pretty disappointed when I finally read the paper as a postgrad. The authors were modern linguists, and they did what modern linguists tend to do: ignore anything done before Chomsky. (In particular, the extensive literature on Balkan and Turkish proverbs done in the philological tradition, through the early twentieth century.) And I knew several equivalent sayings that they had missed, which made me grumble about Deborah Tannen not being a native speaker.

(Yes, *that* Deborah Tannen: she started her academic career with Greek. She end up writing best-sellers looking at men’s and women’s language, after breaking up with her Greek husband—over miscommunications.)

But the common sayings shared between Turkish and Greek only make sense if there were substantial numbers of people bilingual in Turkish and Greek, enough to establish the same sayings either side. This doesn’t accord with the modern Turkish or modern Greek image of Ottoman times; but there is no other sensible explanation.

So, what have we learned?

- We need to be jolted out of our preconceptions on occasion.

- Greek diglossia has a lot of baggage, and therefore carries a lot of preconceptions with it.

- And to jolt those preconceptions, it helps to have library shelves to browse through at random.

Because I don’t have the books at hand, I’m grabbing the online renditions for samples. Here’s Nicander of Corcyra, from the 1841 translation:

Ἅπαντες σχεδόν τοι, πλὴν ἡγεμόνων καὶ τῶν ἔγγιστα βασιλεῖ τυγχανόντων, ἐμπορικὰς μετιᾶσι πράξεις. Καὶ οὐ μόνον ἀνδράσι τοῦτο περίεστι, ἀλλὰ καὶ γυναιξὶν, ὡς ἐπὶ τὸ πλεῖστον, ἐπιγίνεται. Καὶ δαιμονίως ἐς τοῦτο ἐπτοήνται. Καὶ ἦν ἐν ταῖς ἀγοραῖς καὶ ῥύμαις τῆς πόλεως ὁρᾷν γυναῖκας ὑπάνδρους καὶ κόρας, τέχνας τὲ καὶ συναλλαγμοὺς καὶ πράξεις ἐμπορικὰς ἐργαζομένας ἀνυποστόλως. Ἁπλοϊκώτερον δὲ, τὰ πρὸς τὰς γυναῖκας σφίσιν εἴθισται, καὶ ζηλοτυπίας ἄνευ. Φιλοῦσι γὰρ ταύτας ἐν τοῖς στόμασιν, ἀσπασμοῖς καὶ ἀγκαλισμοῖς, οὐχ οἱ συνήθεις καὶ οἰκεῖοι μόνον, ἀλλ’ ἤδη καὶ οἱ μηδέπω ἑωρακότες. Καὶ οὐδαμῶς σφίσιν αἰσχρὸν τοῦτο δοκεῖ.

Almost all, indeed, except the nobles, and those in attendance on the royal person, pursue mercantile concerns. And not only does this appertain to men, but it devolves in a very great extent upon women also. And to this, they are wonderfully addicted. And one may see in the markets and streets of the city married women and damsels employed in arts, and barterings and affairs of trade, undisguisedly. But they display great simplicity and absence of jealousy in their usages towards females. For not only do those who are of the same family and household kiss them on the mouth with salutations and embraces, but even those too who have never seen then. And to themselves this appears by no means indecent.

And here’s Andronikos Noukios, in a sample from the greek-language.gr review of translations from Ancient to Modern Greek:

Λάφι και αμπέλιον

Το λάφι από τους κυνηγούς έφευγεν και εκρύπτη εις αμπέλι. Και όταν απέρασαν οι κυνηγοί, το λάφι ενόμιζεν ότι έγλισεν. Άρχισε να τρώγει εκ τα φύλλα της αμπέλου και, επειδή ανακάτωνε τα φύλλα, εστράφησαν οι κυνηγοί και είδασι το λάφι και το εδόξεψαν. Λοιπόν αποθνήσκοντας έλεγε ότι: «Δίκαια έπαθα, διότι δεν έπρεπε να αδικήσω εκείνην οπού με εφύλαγεν».

Ο μύθος δηλοί ότι όσοι αδικούσιν εκείνους οπού τους ευεργετούσιν, ο θεός τους κολάζει.

Deer and Vineyard

The deer was fleeing the hunters and hid in a vineyard. And when the hunters passed, the deer thought it had escaped. It started eating from the vine leaves, and because it was rustling the leaves, the hunters turned back and saw the deer and shot arrows at it. So dying the deer said: “This serves me right, for I should not have maltreated her who was safegaurding me.”

The fables means that whoever harms those who do them good, God punishes them.

Lerna: Hitler finds out that the Greek language has no more than 200000 words

Travelling as I am in the U.S., I’m going to be light on blogging here at Hellenisteukontos (well, even lighter than usual); any blogging I do is going to be travelogues in The Other Place (once I’m somewhere worth traveloguing about.) But I’ve just found out that Stazybo Horn, honoured member of Team Fortier who has also stopped by and commented here, has taken That Downfall video, and subtitled it… with reference to the Lerna Myth. And a shout out to this Lerna thread! A blessing on your house, Stazy!

(To view Greek subtitles, turn on Closed Captioning, bottom right control next to Volume and Full Screen. My annotated translation into English follows.)

| THEODORE ANDREAKOS,* Educ. Insp. (Ret’d), Hon. Prof. Tech Coll.: The longhairs* are counterattacking. They have occupied WordPress and are heading towards Blogger. They include Sarantakos, Neostipoukeitos, and from the other flank Lexilogia and Periglwssio. From the eastern front, we have opuculuk,* nickel and yannisharis. | Theodore Andreakos: prominent letter-writer in the recent debate in the Athens press over the word count of Greek. longhairs: advocates of Demotic, from their bohemian appearance in the 1900s. opuculuk: opuculuk.blogspot.com, URL of The Other Place, where Yr Obt Svt posts from.

|

| ADOLF: Have Kounadis* attack them, with the ten million words. | Antonis Kounadis: member of the Academy of Athens (representing Engineering), whose April talk on the gajillion words of Greek launched the whole Lerna saga in the Athens press and the blogosphere. |

| THEODORE ANDREAKOS, Educ. Insp. (Ret’d), Hon. Prof. Tech Coll.: Mein Führer… Kounadis… | |

| EURIPIDES STYLIANIDES:* Kounadis is a laughing stock. They’ve reduced the word count to 200,000. | Euripides Stylianidis: Minister for Education in 2008, taken in by the Lernaean Myth in a speech. Notoriously, the speech included a folk etymology of έντερο “intestine” as ἐντὸς ῤέω “I flow within” |

| ADOLF: … The following will stay behind. Andreakos, Kounadis, Stylianidis, and Adonis-Spyros.* | Adonis Georgiadis: Greek right wing politician, publisher, author, and TV host. Prominent in nationalist philippics on the Greek language. His original name is Spyros, and his critics delight in pointing out the affectation of his name change. |

| ADOLF: FUCK MY IN-TEST-INE!* We’d talked through Kounadis’ mission! How did he manage to mess it up?! What do I keep collecting Liddel–Scotts for him for? You’ve forgotten all your graves and rough breathings*—I won’t even mention your iota subscripts! You can’t recite a single iamb in Aeolic! | in-test-ine: See above, έντερο. Graves and rough breathings: the polytonic accentuation system, a rallying point of linguistic conservatives after the disuse of Puristic Greek. |

| ADONIS GEORGIADIS: The man of many devices…* | The man of many devices : the beginning of the Odyssey: Iambic in Modern Greek translation, at least. |

| ADOLF: We’d already got up to 120 million words! | |

| ADONIS GEORGIADIS: Mein Führer, Euripy did try… | |

| ADOLF: The TLG says as much! 5,000,000 words! Even English has overtaken us! What the fuck are you learning in your academies anyway? Just how to stick clubs up omegas’ privates?* Sarantakoses and Tipoukeitoses! They should be impaled on the Colossus’ torch! Hanged on the Themistoclean Walls! Them and Maria and Diver and Pi-Squared. And that Stazy. | clubs up omegas’ privates: A humorous verse in 1964 by Dinos Christianopoulos lamented that the abolition of iota subscript would deprive the Greek script of “its smallest obscenity”: omega with iota subscript, ῳ, which looks slightly like a depiction of anal sex if your mind is dirty enough. With the iota subscript long abolished, the verse is routinely brought up in any discussion of the polytonic. |

| I never went to any academies. But I have glorified my language, by turning the world into mincemeat. Linguists! What did I sit and learn duals and infinitives for? 120 volumes,* I read them one by one. I even read about the God of the Jews.* He too was in my language. Millions of words; not one fewer! | 120 volumes: As was pointed out in the letter-writing saga, if Greek really did have five million words, Liddell-Scott would have 120 volumes, not just one (or two, depending on the edition). God of the Jews: The Septuagint is included in the TLG corpus. |

| SECRETARY: Hush, Lady Madonna…* | Hush, Lady Madonna: Despina “Madonna” is a plausible first name, but this is an allusion to the folksong verse beloved of Greek irredentists: “Hush, Lady Madonna, and cry not so; after years and times pass, they will be ours once more.” The song gave its title to Herzfeld’s influential critique of the politicisation of Greek folklore |

| ADOLF: A pity I copied so much just to break my hand in.* Now where will I find 60 million terms? That’s it. We’ve dipped the boat. Sarantakos has pulled our pants down. But if you think I’m going to start using monotonic accentuation, you’re mistaken. I’d rather lick a kouros’ “pears”.* 200,000 words, he says… | to break my hand in: An allusion to a comment by Cornelius, the polytonicist gadfly of Sarantakos’ blog, that he used to voluntarily copy out polytonic texts in school “to break his hand in”, gratified to find Babiniotis is now recommending the same. “My mother would say that was contrary to any paedagogical principle; I replied it was the monotonic system that was contrary.” pears: απίδια, euphemism for αρχίδια “balls” |

The 23 to 29 Apolloniuses of Classical Literature

I’m parking this posting here for lack of somewhere else to park it. (It’s not strictly language-related, but I’m realising philology posts are probably better pitched here than in The Other Place.)

In my day-job capacity, I’m posting on the fluidity of identity in repositories—how, particularly if you’re relying on computer deduplication of identity, there will always be some tentativeness about who is identified as the same person. Repositories have to deal with that tentativeness, rather than hardcoding identity. This is an issue Wikipedia often comes up against, having to split off one article subject from another.

And I was reminded of the morass of Apolloniuses in Classical literature, particularly among medical authors. There are no less than potentially 13 medical authors we know of called Apollonius, according to the TLG Canon of Greek Authors and Works (3rd ed.). Potentially 13, potentially just 9; f.i.q. “possibly the same person as”, appears several times in the listing:

- 0680 Apollonius of Memphis, iii BC, cited in Galen

- 0741 Apollonius f.i.q. Apollonius of Memphis, iii BC?, cited in Aëtius

- 0660 Apollonius of Citium, i BC

- 0792 Apollonius of Pergamum, I AD?, cited in Oribasius

- 0739 Apollonius f.i.q. Apollonius of Citium or Apollonius of Pergamum, i BC/I AD?, cited in Alexander of Tralles

- 0789 Claudius Apollonius, I AD, cited in Galen

- 0747 Apollonius Archistrator, f.i.q. Claudius Apollonius, I AD?, cited in Galen

- 0782 Apollonius of Tarsus, before II AD, cited in Galen

- 0810 Apollonius &

- Alcimion, I AD, cited in Galen

- 0790 Apollonius Mys, i BC

- ?? Apollonius Opsis

- 0817 Apollonius Organicus, f.i.q. Apollonius Opsis, i BC?, cited in Galen

- 0791 Apollonius Ther, f.i.q. Apollonius Opsis, i BC?, cited in Oribasius

(Note: links are to the Catalan Wikipedia.)

Our problem in working out who is who is that almost all of them are cited in passing in other medical authors, so we have very little to go on. The Online TLG Canon only represents works published under a distinct author’s name, even if only as Testimonia. So it only refers to two of them, Of Citium and Mys. The other 11 authors also have Testimonia, in Galen and Oribasius and Alexander of Tralles and Aëtius, but they haven’t been published independently.

So the 2009 Online Canon has more limited coverage of types of author than the 1990 Print Canon (though a longer time range). The Print Canon includes all ancient authors we know about. The Online Canon only includes those authors with texts represented in the corpus, and that is determined by an editor publishing text under that author’s name. So if an Apollonius has been cited in Galen, and an editor publishes that citation as a Fragment of Apollonius, Apollonius will have an entry in the Online Canon, and will link to the published text in the corpus. If we only have secondary source material on the Apollonius from Galen, and an editor publishes that material as Testimonia on Apollonius, the Online Canon will still have an entry, because the point of the author entry is to navigate the corpus.

If OTOH an editor has never combed Galen for Apollonius, the Print Canon will still mention the Apollonius as cited in Galen (as a cross-reference), but the Online Canon will not have an entry for him, because it doesn’t have a discrete text for him. That places the Online Canon notion of authors at the mercy of their editorial history; but the Online Canon is documenting edited texts.

The 9–13 medical Apolloniuses in the TLG Canon are joined there by 16 other Apolloniuses in Ancient literature:

- 1167 Apollonius (Biographer), wrote a Life of Aeschines

- 0394 Apollonius (Comic)

- 1404 Apollonius (Grammarian)

- 1170 Apollonius of Aphrodisia, historian

- 1169 Apollonius of Athens, another historian

- 2283 Apollonius, yet another historian

- ?? Apollonius (a mathematician), f.i.q. Apollonius of Tyana, putative author of the Apocalypse of Adam

- 0569 Apollonius (Paradoxographer)

- 0550 Apollonius of Perga, mathematician

- 0619 Apollonius of Tyana, philosopher

- 1171 Apollonius of Ephesus, theologian

- 1168 Apollonius the Sophist, author of Homeric Lexicon

- 4259 Apollonius Cronus, philosopher

- 0082 Apollonius Dyscolus, grammarian

- 2491 Apollonius Molon, historian

- 0001 Apollonius of Rhodes, Epic poet

The English Wikipedia knows of 16 non-medical Apolloniuses (but five of them are not in the list above), and no less than 21 physicians called Apollonius, since they’re not restricted to medical authors. And Wikipedia is just as aware of the f.i.q. issue. The German Wikipedia’s list has 24 Apolloniuses, and they don’t seem to overlap completely with the English list. The Catalan Wikipedia’s list wins, with 18 medical and 39 non-medical Apolloniuses. And its list is even less clean.

Even adding in places of birth, nicknames, and the genres they wrote in, there is difficulty in differentiating these Apolloniuses. If we had enough metadata on them, after all, instead of passing mentions in Galen, we wouldn’t be seeing all those f.i.q. For 0741 Apollonius and 0739 Apollonius, we’re reduced to distinguishing them by who else they might be confused with. And the medical Apolloniuses may all be obscure (only Of Citium gets his own English Wikipedia page); but the other Apolloniuses include a major Late Epic poet (0001), the founder of Western grammar (0082), a major figure in Roman religious history (0619), a primary source in Homeric scholarship (1168), and an important contributor to the development of 3D geometry (0550). If it wasn’t for places of birth and nicknames, we would not know who we were talking about.

Things are slightly better now with the invention of surnames, and recording years of birth in the Library of Congress record. But only slightly: confusion is certainly still possible. There is now a profusion of identities that people write under in cyberspace; if anything, that’s now making things even worse. But that’s a topic for my day-job blog…

The Motley Word

I continue the random miscellanea postings with a website I did not know about, and stumbled on because of a posting I will write next week. The Motley Word (Παρδαλή Λέξη) is a crowdsourced dictionary for Greek dialects, like Urban Dictionary and its Greek counterpart, slang.gr

The Motley Word has all the poor quality you’d expect of a crowdsourced project without critical mass of participants; they don’t even provide for correction yet. So it’s not going to supplant the Academy’s dialect dictionary, the Historical Dictionary Of Modern Greek, any time soon. Sure.

But that’s harder to say when the Historical Dictionary hasn’t budged past delta in twenty years. (I see there’s at least funding to digitise their holdings.) And the glossaries of mainstream dialects, as opposed to the more distinct variants like Pontic or Tsakonian, have been pretty motley themselves.

More meta-importantly, the Motley Word shows that speakers of the dialects still care, and it’s still a resource. A resource I’m going to make use of soon—here’s a hint, but I haven’t started writing yet, so shhhhh…

So: excellent work! (And thank God noone’s done Tsakonian 🙂

Heracleses of the Crown

I don’t want to get into the habit of retweeting what other bloggers say, it was annoying enough when Instapundit and Atrios started doing it. I also don’t want this blog to get *too* Classicist-friendly, because there’s plenty of Modern Greece stuff to talk about that has nothing to do with The Antick Burden. But this novel form commented on at The Magnificent Nikos Sarantakos’ Blog is too interesting not to pass on to Classicists.

(And yes, I get much of my material from Sarantakos. That’s why I keep calling the blog The Magnificent. That, and I like establishing a private language; hence “The Other Place”.)

One of Sarantakos’ concerns is good language use. So he lampoons instances in the press or from politicians of bad language use. What good and bad language use is of course a prescriptive matter—and I have to say, I’m pretty much cured of the anti-prescriptivism of linguistic orthodoxy: prescriptivisms can have their own internal linguistic reality, and they certainly have a social reality. Prescriptivism in Modern Greek is complicated, like the language itself is. It’s no longer about how Attic a form is; now it’s about how vernacular a form is, how glaring a translationism from English it is, or how boneheaded a misapplication of Attic it is.

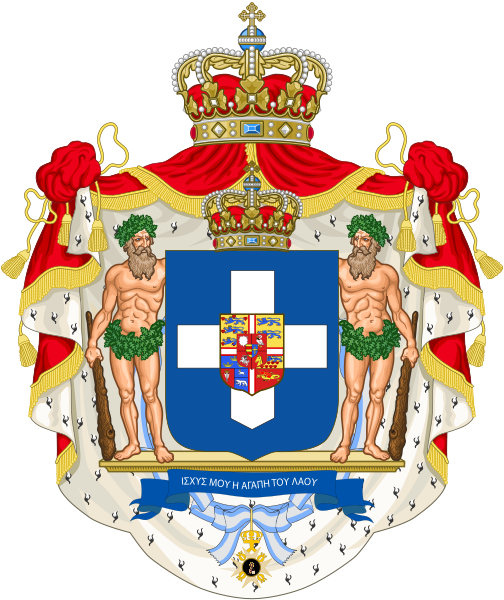

The “first linguistic gaffe after the elections”, taken across by Sarantakos from a thread from Nikos Ligris in lexilogia.gr, was a politician’s disparaging reference to two major members of the outgoing government. He called them The Heracleses of the Crown, using an established metaphor referring to the old coat of arms of the Kingdom of Greece:

But the plural of Heracles he used was not the Classical Ἡρακλεῖς. Nor was it the vernacular Ηρακλήδες.

(I’ve already posted on why that is the plural formation for vernacular first-declension nouns. Yes, Heracles is now first declension: the third declension is dead in the vernacular. And yes, that plural *is* historically still third-declension, because the declensions hybridised.)

No, the plural form the politician used was οι Ηρακλειδείς του στέμματος.

Now, Ἡρακλειδεῖς is in no way a plural of Ἡρακλῆς. It is a plural of *Ἡρακλειδεύς, and the -ιδεύς suffix on that word was used in antiquity to denote the offspring of an animal or a family member: ἀετιδεύς “young eagle”, λυκιδεύς “young wolf”, υἱιδεύς “son of a son”, γαμβριδεύς “son of a brother in law”. LSJ has one inanimate diminutive use in an inscription, θυριδεύς “little gate = window frame”, and the most widespread use of the suffix is also diminutive rather than offspring: ἐρωτιδεύς “cupid, depiction of Eros [Cupid] in sculpture or painting”. But there is no Ancient use of the suffix as a patronymic: the Offspring of Heracles are the Heracleidae, Ἡρακλεῖδαι.

It turns out though that the fans of Heracles FC, the oldest football club in Thessalonica, have taken to calling themselves Ηρακλειδείς. Amused by their claims to antiquity, rather than to actually winning championships, fans of Ares FC and PAOK FC have taken to calling them “The Old Ladies” instead.

So we can reconstruct what happened. An Attic plural Ηρακλείς in Modern Greek is hopeless: it is homophonous with the singular Ηρακλής [iraˈklis], and it uses a third declension noone has heard of. (They would especially not have heard of it because this particular declension pattern in -κλῆς is restricted to proper names, and plurals of proper names are rare.) A vernacular plural Ηρακλήδες is still felt undignified: you can use it about your cousins called Heracles, or to express contempt about the Heracleses and Theseuses of legend (and it sounds as clunky as Heracleses does in English); but the fans of Heracles FC would never refer to themselves so commonly.

(They would have decided that in the phone booth they meet in every Saturday, as an Ares FC fan might put it.)

Confronted with the lack of a useable *and* appropriate plural of Heracles, a Heracles fan a few years ago hit on the pattern of ἀετιδεύς “young eagle”, and started people using Ηρακλειδείς. Ηρακλειδείς is in a third declension just as dead in Modern Greek, but at least somewhat more familiar via Puristic.

- (As also noted in comments, the colloquial singular of that word is not Ηρακλειδεύς, but Ηρακλειδής. Because the third declension in -ευς is not *that* familiar.)

- (E-fufutos [as he Englishes himself] says ἀετιδεύς is “familiar to all those who learned about 19th Century France via Puristic writers.” Who was the French Eaglet?)

The Heracleses of the Crown in the coat of arms have always been Ἡρακλεῖς. The politician being interviewed racked his brain for a plural of Heracles—which as we saw, is awkward in Modern Greek. He remembered Heracles FC, made the association between ἐρωτιδεῖς “little cupids” and the little heraldic club-bearers, and blurted out Ηρακλειδείς. Some commenters to the thread admitted that they have done the same.

So, was this a gaffe? There’s a disagreement in the commentary to the post.

Opinion 1 (Nikos Sarantakos, Nikos “Nickel” Ligris): Yes, it’s a malapropism: an attempt to coin a la-de-da Classical plural that ends up stumbling on an unattested word that violates Classical norms, and has nothing to do with Modern Greek at any rate.

Opinion 2 (“Boukanieros”, me, Tasos “TAK” Kaplanis): It’s a new word, and it’s adorable. The analogy with cupids is clear in this particular context, and the Classical norm of it not being attached to proper names is not relevant here.

Opinion 1: What’s so “adorable” about a bastard learnèd form?

Opinion 2: There’s been a lot worse in the Athens press than Ηρακλειδείς. The Heracles FC context makes it attested, at any rate.

Opinion 1: The bastard form Ηρακλειδείς is indeed now attested for the fans (my spellchecker does not underline it!) Can we at least leave alone the established word for the coat of arms?

Opinion 2: But they’re wee little Heracleses on the coat of arms! [You’ll see the vernacular diminutive, Ηρακλάκια, more than once in the thread]

Opinion 1: There’s this notion that as soon as any fool launches some half-baked variant form online, we’ve got to annotate it and put it into our dictionaries, instead of “correcting” it. (There’s those PC scare-quotes again.)

Opinion 2: Yup. [My Anglophone readers are nodding along heartily, but note that the social histories of English and Greek are very different, and distaste for prescriptivism in English does not have the same purchase in Greece.]

The thread is ongoing, although I think people are agreeing to disagree by now. (The thread is now being derailed to talking about the Orwellian names of the new government’s ministries.) I don’t remember this much disagreement in a thread about linguistic gaffes recently, and I think it is because Opinion 1 and Opinion 2 are analysing the form differently.

Opinion 1 considers it a mistaken stab at a plural of Heracles that coins a new word by mistake. Opinion 2 considers it a serendipitous coining of a new word, that can in some contexts stand in as a plural of Heracles.

Opinion 1 considers the coinage illegitimate, as pseudo-archaic Greek in a time when pseudo-archaic Greek is no longer welcome. Opinion 2 shrugs.

Nikos will defend Opinion 1 more cogently than I have done, I suspect, because there is context to notions of correctness in Modern Greek that I’m not fully presenting here…

Deictic force of Hellenistic demonstratives

Quick note: Ἐν Ἐφέσῳ notices from the linguistics literature that the meaning of demonstratives in Modern Greek depends on their position: αυτό το μπουτάκι “that-one the pork-joint” is more physical deixis (“that pork joint which I’m pointing at”), whereas το μπουτάκι αυτό “the pork-joint that-one” is more discourse deixis (“that pork joint which I mentioned before”).

He considers this may shed light on the use of demonstratives in New Testament Greek—and commenter Carl Conrad notes this is already known of Classical Greek, complete with Smyth reference.

Nastratios in Pagdatia

A thread last month at the Magnificent Nikos Sarantakos’ Blog, about insulting commentary on a candidate MP from the Muslim minority, got derailed in comments (the way good comment threads do) into a discussion of whether there was any point teaching Ancient Greek in high school in Greece. The reason why Ancient Greek is taught in high school has to do with moral panic, rather than any concern over actually learning the language. That is why the age at which it is taught has become such a football; and the way Ancient Greek is taught is universally condemned.

Indeed, most commenters thought teaching Ancient Greek language at the expense of Ancient Greek literature *as literature* was unacceptable, and teaching Ancient literature in translation, as has occasionally happened, is much preferable. Some commenters conceded the usefulness of Ancient Greek in teaching grammar, but grudgingly. And I’ll stay with this exchange:

Ηλεφούφουτος: … Instruction should not give so much emphasis on reproducing grammatical forms (e.g. what is the 3rd person imperfect of ὑφίημι, or conjugate the verb in the second aorist middle optative.) All that, and syntactic parsing word for word, are fine brain exercises, but that’s now how you’ll learn Ancient Greek.

Μαρία: Who gives a f*ck about reduplication. But for students to recognise that this is a verb, an adjective, at least the parts of speech: that much is necessary. So they must be taught grammar, and you can’t do that with little songs and little poems. Have you forgotten this isn’t a living language?

I’m not contributing to that derailment—although I agreed there it was absurd that the students weren’t being asked questions about the literary values of Antigone. In fact, the recommendations Ηλεφούφουτος was citing included “don’t teach Ancient Greek through Antigone, you’ll ruin Antigone for the kids.” But I’m doing my own derailment, with the notion of little songs and little poems in learning Ancient Greek—that is, of teaching Ancient Greek in the engaging way schoolchildren learn foreign languages.

There is a textbook that does that: Paula Saffire & Catherine Freis. 1999. Ancient Greek Alive. 3rd ed. Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press.

Ancient Greek Alive has students act out skits, it has them doing question and answers with the teacher in Ancient Greek, and it has little stories in the target language, rather than starting with Real Text. In other words, it does what you normally do nowadays when you teach a foreign language. It would never ever be used in Greece, not only because of the profound malaise of Greek education, but because the relation of Greeks to their antiquity has always been too po-faced. It’s the same reason, as I’ve posted in The Other Place, why a Greek will never affectionately parody their national anthem the way the Dutch do; and why a pastiche like Geoffrey Chaucer Hath a Blog will not lead to a Ἱστολογίζει Θουκυδίδης blog or a Λουκιανοῦ Διαδικτυακτοὶ Διάλογοι blog. At least not by a Greek.

(I beg someone to prove me wrong.)

I was reminded of Ancient Greek Alive because the earliest little texts it puts to the student are nothing to do with Ancient Greece. They are translations of tales of Nasrudin. Nasrudin is a comic figure from the Sufi tradition, who has made it into the folklore of many Muslim countries and their neighbours. His humour is somewhat subversive, and delightfully absurdist.

One of the neighbouring peoples Nasrudin’s japes have gone across to are the Modern Greeks. He survives more in Cyprus than in Greece, but his humour has remained proverbial, in “the argument over the blanket” if nothing else—which has become a journalistic cliché. Nikos Pilavios’ Greek Fairy Tale blog (I vaguely remember watching his TV show when I was a kid) has 36 Nasrudin tales, and an article about his own discovery of Nasrudin. Not all the tales are authentic, but authenticity doesn’t mean that much with fairy tales. The journalistic cliché instance of a Nasrudin story, however, has been contributed there by a commenter:

Ενα βράδυ ο Ναστραντίν Χότζας κοιμόταν με την γυναίκα του. Ξαφνικά ξύπνησε από τις φωνές δύο ανθρώπων που καβγάδιζαν κάτω από το παράθυρό του. Σηκώθηκε, τυλίχτηκε στο πάπλωμα και κατέβηκε να δει τι συμβαίνει. Μόλις αυτοί τον είδαν, παράτησαν τον καβγά, άρπαξαν το πάπλωμα και έγιναν καπνός. Οταν η γυναίκα του τον ρώτησε γιατί καβγάδιζαν, της απάντησε: «Ο καβγάς ήταν για το πάπλωμα».

One evening Nastrandin Hodja was sleeping with his wife. Suddenly he woke to the shouting of two men arguing beneath his window. He got up, wrapped himself in his blanket, and went downstairs to see what was happening. As soon as they saw him, they quit arguing, grabbed the blanket and disappeared. When his wife asked him why they were arguing, he answered: “the argument was over the blanket”.

Have you noticed what’s happened to the name Nasrudin? It starts in Arabic as نصرالدين naṣr ad-dīn, “Victory of the Faith”, which is a Muslim proper name. In Turkish, it’s Nasreddin Hoca, Teacher Nasreddin. Greek now respectfully transliterates him as Νασρεντίν <Nasrentin>; but spoken Greek had no patience for /sr/ clusters, so traditionally he has been called Ναστραντίν Χότζας, <Nastrantín Chótzas>, with an epenthesis breaking up the /sr/.

I was reminded of Nastrantin, not because of the thread over at Sarantakos’, but because I came up against the name in a different context. I’ve been going through the Prosopographisches Lexikon der Paläologenzeit, the Who’s Who of Late Byzantium; and I’ve found that George Pachymeres mentioned a Nasreddin Mahmud, son of Muzaffer ed-din Yavlak Arslan, who died in the battle of Bapheus in 1302. Because written Greek had no patience for /sr/ clusters either, he is rendered as <Nastrátios>, with the same epenthesis:

Ἁλῆς γὰρ Ἀμούριος σὺν ἀδελφῷ Ναστρατίῳ τῷ παρὰ Ῥωμαίοις ἐπὶ χρόνοις ὁμηρεύσαντι, τοὺς περὶ τὴν Καστάμονα Πέρσας προσεταιρισάμενος, Ῥωμαίους κακῶς ἐποίει.

For Amurios Hales [“Amur” Ali Bey], with his brother Nastratios who had been a hostage with the Romans for years, joined the Persians [Turks] around Kastamon [Kastamonu], and did ill to the Romans. (p. 327 Bekker)

Hold on to that Hellenisation as <Nastratios>, we’ll come back to it. It gets worse in the Palaeologan Prosopography, btw. Ducas mentions a Χατζιαβάτης, Haci Aivat. Not the same person as the Hacivat of Turkish shadow puppetry, but certainly the same Hellenisation in its Greek counterpart.

What possessed Paula Saffire to insert a Sufi jokester into an Ancient Greek textbook? You can read all about it at her website. The notion of a Turkish jokester turning up in an Ancient Greek textbook is, I think you can safely surmise, a notion some Greeks are likely to have issues with: one more reason you won’t see Ancient Greek Alive taken up in Greece. More’s the pity.

So far, I’ve cited Nastrantin in Modern Greek, and a different Nastratios in Byzantine Greek, but I haven’t shown you how Saffire & Freis Greek Nasruddin in the textbook. Here’s his first appearance, p. 28:

ἄνθρωπός τις βούλεται πέμπειν ἐπιστολὴν ταῖς ἀδελφαῖς ταῖς ἐν τῇ Βάγδαδ. ἀλλὰ οὐκ ἐπίσταται γράφειν τὰ γράμματα. αἰτεῖ οὖν Νασρέδδινον τὸν Σοφὸν γράφειν τὴν ἐπιστολήν. ὁ δὲ Νασρέδδινος λέγει αὐτῷ· «ὦ φίλε, οὐκ ἐθέλω γράφειν τὴν ἐπιστολήν. οὐ γάρ ἐστί μοι σχολὴ πορεύεσθαι εἰς τὴν Βάγδαδ.»

ὁ δὲ ἄνθρωπος λέγει «ἀλλὰ οὐκ αἰτῶ σε πορεύεσθαι εἰς τὴν Βάγδαδ. αἰτῶ σε μόνον ἐπιστολὴν γράφειν ταῖς ἀδελφαῖς μου.»

«οἶδα» ἀποκρίνεται ὁ Σοφὸς· «ἀλλὰ ἡ γραφή μου κακή ἐστι καὶ ἀνάγκη ἂν εἴη μοι πορεύεσθαι εἰς τὴν Βάγδαδ καὶ ἀναγινώσκειν αὐταῖς τὴν ἐπιστολήν.»

A man wants to send a letter to his sisters in Baghdad. But he does not know how to write the letters. So he asks Nasreddinos the Sage to write the letter. But Nasreddinos says to him: “Friend, I do not want to write the letter. I don’t have enough time to go to Baghdad.

The man says, “but I’m not asking you to go to Baghdad. I’m only asking you write a letter to my sisters.”

“I know,” the Sage answers. “But my handwriting is bad, and I would have to go to Baghdad myself and read the letter out to them.”

You may have noticed some things wrong. No, they have not taught the aorist yet, so everything is in the present tense; that’s understandable, though it makes the story sound Pontic. (No, not Pontic as in the butt of Greek jokes, but as in the dialect that fails to make any aspect distinctions in the subjunctive.) I’m also not sure that’s how you’d use οἶδα. But no, there’s something wrong with the transliteration.

Not that they failed to use <Nastratios>: it would hardly be fair to ask that of them—although the fact that they, like contemporary Greeks, have patience for /sr/ clusters puts them at odds with what a Greek writer would actually have done.

But what sticks out, as many a Greek will tell you, is Βάγδαδ <Bágdad>. Greeks do not call Baghdad Bagdad /ˈvaɣðað/. They call it Βαγδάτη, <Bagdátē> /vaɣˈðati/. And they will become righteously indignant, as indeed I did when I bought the book. We met Iraqis centuries before the Beef-Eaters—and Theophanes Confessor called them Hērakîtai, Ἡρακῖται. Where do Saffire & Freis get off, ignoring what Greeks call Bagdad, and coming up with their own name? Don’t we matter? Don’t the Byzantines, who dealt with Bagdad, matter?

The sentiment has a certain sense behind it; to call Russians Ῥοῦσσοι instead of Ῥῶσσοι, as they do elsewhere (moving on to an anecdote about Napoleon) does seem a little disrespectful of Constantine Porphyrogenitus.

But I’ve already written a post on how Modern Greek Hellenisations are more antiquarian than Byzantine Hellenisations were. So how did those Byzantines actually call the city?

- Theophanes Confessor (ix AD): Bágda

- Apomasar (ix AD): Bagdân

- Leo Choerosphactes (x AD): Bagdá

- Constantine Porphyrogenitus (x AD): Bagdád

- Theophanes Continued (x AD): Bagdá, Bagdád

- Anna Comnena (xii AD): Bagdâ

- John Scylitzes (xii AD): Bagdá

- John Zonaras (xii AD): Bagdâ

- Digenes Acrites (xiv AD): Bagdâ

- Laonicus Chalcocondyles (xv AD): Pagdatíē, Pagdátin

- Vernacular Astrological texts, Delatte: Codices Athenienses (? AD): Bagdádai, Pagdáti

The accentuation Βάγδαδ has never been correct: Saffire & Freis have carried across the Germanic stress position of English /ˈbæɡdæd/, whereas all but the first Greek transliteration reflect the stress of the Arabic بغداد /baɣˈdaːd/.

But it turns out there is nothing Byzantine about the modern feminine form Βαγδάτη. The Byzantine forms are either variants of the feminine Βαγδά, the neuter Παγδάτι, or the quite indeclinable Βαγδάδ, with the hesitation between <b> /v/ and <p> /p/ typical of Late Byzantium. (Chalcocondyles’ Homeric rendering of “Bagdadia”, Παγδατίη, is the kind of affectation we’d expect of him.) I couldn’t find out from my quick-and-obvious search when Βαγδάτη was first used, but it doesn’t seem to be have been used by those who met Iraqis centuries before the Beef-Eaters.

Attempts to write Ancient Greek in Modern times, à la Neo-Latin, don’t have a convenient name, through which the Ancient Greek Wikipedia can be banned by the Wikipedia Language Committee (grumble stick-up-their-arses grumble as-if-anyone-uses-Low-Saxon-as-a-primary-language-of-communication grumble grumble). We can’t call them Neo-Greek, Neohellenic is what Modern Greek is called. Neo-Classical goes to Stravinsky—or Puristic. Neo-Attic is too specific, it leaves out the Astronautilia. Neo-Ancient?

Whatever it’s called, Neo-Ancient Greek when it happens is indebted to Puristic: the Ancient Greek Harry Potter doffs its hat to 19th century dictionaries (and shies away once Demotic turns up in the lexica). The Neo-Ancient Greek Asterix doesn’t doff its hat, admittedly. Then again, the Neo-Ancient Greek Asterix doesn’t have to: it was translated in Greece (ingeniously), and Puristic seeps in there through the soil.

(The linked post notes that Asterikios in Ancient Greek didn’t work well with Grade 7 students, who still struggled with the language—but that it did work when accompanied by the Modern Greek text in parallel. While we’re on the subject: two interviews with the translator of Asterix into Ancient Greek, Fanis Kakridis: #1, #2.)

Saffire & Freis did not doff their hat to Puristic either, in telling tales of Napoleon or Nasrudin—even through they drafted the textbook on a beach in Crete. (Maybe Puristic doesn’t seep through sand.) So their Russians are Ῥοῦσσοι instead of Ῥῶσσοι, because of English Russian, and their Nasrudin is Νασρέδδινος because of Turkish Nasreddin, not Modern Ναστραντίν. (It would have been unreasonable, I admit, to demand of them Mediaeval Ναστράτιος.)

In not writing Βαγδάτη, though, it wasn’t the Byzantines they didn’t doff their hat to, it was Puristic, and by extension Modern Greek. But of course, when Harry Potter uses Puristic words, it isn’t because of love of Coray and Papadiamantis. It’s because that’s where he’s going to get a word for train more compatible with Ancient Greek than the contemporary τρένο. Saffire & Freis had no such compulsion with Modern names.

The failure to epenthesise <Nasréddinos>, I’d still say, is a lack of sensitivity to Ancient Greek as a spoken language, which is ironic given how oral their textbook is. But the extremely unpleasant truth is, an American textbook of Ancient Greek owes Modern Greek speakers even less than it does to Constantine Porphyrogenitus. It doesn’t owe them Βαγδάτη just as it doesn’t owe them iotacism.

Still, if it owes the Hērakîtai anything, it’s not Βάγδαδ. Like Constantine Porphyrogenitus said: it’s Βαγδάδ.

P.S. Saffire has made the mistake of saying on her website: “Surely these are the only Sufi stories in ancient Greek!”

Them’s fighting words:

ἀφικόντος γείτονος ἐπὶ τῆς πύλης Ναστρατίου τοῦ ἱερέως, ἐξέρχεται ὁ ἱερεύς ὑπαντῆσαι αὐτόν.

«δός μοι, ἱερεῦ, τὸν σὸν ὄνον σήμερον», αἰτεῖ ὁ γείτων. «ἔχω γὰρ ἀγαθά φορτία τινα μετακομῆσαι εἰς τὴν ἄλλην πόλιν.»

ὁ μὲν Ναστράτιος οὐ βούλεται δοῦναι τὸ κτῆνος οὕτῳ τούτῳ· ἵνα δὲ μὴ ἄξεστος φανῇ, ἀποκρίνεται·

«σύγγνωθι, ἀλλ’ ἤδη δέδωκα τὸν ὄνον ἑτέρῳ.»

αἴφνης ἀκούεται ὁ ὄνος ὀπίσω τοῦ τείχους τῆς αὐλῆς ὀγκώμενος.

«ἐψεύσθσης μήν μοι ἱερεῦ!» φωνεῖ γείτων. «ἤν, ὀπίσω τοῦ τείχους!»

«ποῦ δαὶ τοῦτά φῃς;» ἀποκρίνεται ὁ ἱερεύς βριμώμενος. «τίνα δὴ μᾶλλον πιστεύσεις, ὄνον ἢ τὸν σὸν ἱερέα;»A neighbour comes to the gate of Mulla Nasrudin’s yard. The Mulla goes out to meet him outside.

“Would you mind, Mulla,” the neighbour asks, “lending me your donkey today? I have some goods to transport to the next town.”

The Mulla doesn’t feel inclined to lend out the animal to that particular man, however; so, not to seem rude, he answers:

“I’m sorry, but I’ve already lent him to somebody else.”

Suddenly the donkey can be heard braying loudly behind the wall of the yard.

“You lied to me, Mulla!” the neighbour exclaims. “There it is behind that wall!”

“What do you mean?” the Mulla replies indignantly. “Whom would you rather believe, a donkey or your Mulla?” (via Wikipedia)

I welcome chastisement of my Neo-Ancient Greek in comments. Well, chastisement within reason…

[EDIT: I got better than chastisement from William Annis; I got an improvement. In iambics after Babrius. I’d pardon his violation of Porson’s Law, but my command of Ancient Greek is so lacking—let alone metrics—that I cannot but reverently cede the floor to him:]

γείτων τις αὐλῆς ἦλθε Ναστρατίου πύλην,

ὁ δ’ ἐκτὸς ἦλθεν ἀσπάσασθαι γείτονα.

“βούλοι’ ἂν, ἱερεῦ,” δεόμενος ἔφη γείτων,

“τῇδ’ ἡμέρᾳ μοι τὸν ὄνον ἐνδοῦναι τὸν σόν;

εἰς γὰρ πόλιν πρόσοικον ἐμπολὰς οἴσω.”

ἀλλ’ οὔτ’ ὄνον βουλόμενος ἐνδοῦναι κείνῳ,

οὔτ’ εἰκέναι γ’ ἄγροικος, ἠμείφθη λέγων,

“σύγγνοιαν ἴσχ’, ὦ γεῖτον, ἄλλῳ γὰρ πόρον.”

τείχους δ’ ὄπισθ’ ἔκλαγξεν ὄνος εὐθὺς μέγα.

“ἔψευδες ἄρα μοι,” φὰς ἐβόησεν γείτων,

“ὧδε γὰρ ὄνος πάρεστι!” ἱερεὺς δ’ ἤχθετο·

“πῶς οὖν λέγεις,” ἔλεξε, “τίνι δῆτα πείθου;”