Subscribe to Blog via Email

Join 329 other subscribersMarch 2026 M T W T F S S 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 22 23 24 25 26 27 28 29 30 31

Can we exclude that in the not so distant past Tsakonian was familiar to those from North of Sparta to South East of the Arcadian capital Tripoli?

We can’t exclude it.

Tsakonian is an absurdly archaic variant of Greek, and that speaks to long-term isolation from the rest of the Greek speaking world. It would have to be longer-term isolation than Old Athenian, the cover-term for the enclaves of Greek (Athens, Aegina, Megara, Kyme) blocked off from the rest of the Greek-speaking world by the arrival of ethnic Albanians after the Black Death.

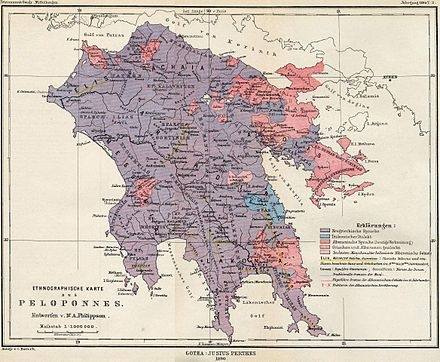

Modern day Tsakonia (the blue bit in this 1890 map) has a coastal bit in Leonidio, but it was cut off from the north through mountains, and the coastal approach required porters to wade out and carry luggage in 1895. You’ll notice that the surrounding areas are purple, not pink (Arvanitika-speaking); the ethnic Albanians were not the reason for Tsakonian being isolated.

We have a few pieces of evidence about Tsakonia formerly. We know from Mazaris’ Journey to Hades, written in the 1400s, that some people in the Peloponnese spoke unintelligible gibberish; earlier on scholars thought that was a reference to Tsakonian, but the surmise is now that it refers to Mani, a (less) archaic variant of Greek spoken in the Middle Finger of the Peloponnese.

We know that when Evliya Çelebi recorded some words of Tsakonian in the 1660s, he was in an area far to the south of Modern Tsakonia. (I don’t remember, but I think it was near Monemvasia.)

And we know that Vatika, at the bottom of the right southern finger of the Peloponnese and near Monemvasia, has almost the same name as Vatka (in Turkish, Misakça), where there was a Tsakonian colony up until 1915. (They were deported to the interior of Anatolia because of WWI, before the 1922 population exchanges.)

What would a native Greek speaker differ in if they spoke French, dialect, tone, or accent? Would there be a difference?

… You know, I’ll take the challenge.

I have a PhD in linguistics and I know the IPA backwards, but my accent in foreign languages is horridly Greek.

From Nick Nicholas’ answer to What does Genesis 1:1-3 sound like in your language? : Vocaroo | Voice message

Don’t assume that polyglots always have a great accent. I know a polyglot prodigy who has recently showed up on this site, so I won’t name him: he knows a dozen languages, and he sounds Bulgarian in all of them. You have to be immersed in a country for a fair while to pick up the accent with some fluency.

As both other answerers have pointed out, there would be shibboleths. The uvular [ʀ] would end up a velar [ɣ] or a trilled [r] (the former is likelier unless the speaker had never heard anyone speak French). The rounded front vowels, the [œ, y], would be way too close to /e/ and /i/. They’d have trouble with the [ɥ]. (Doesn’t everyone?) I think they’d do a passable [ʃ, ʒ], but their nasals would be hit and miss. And of course, they’d have the rat-tat-tat of a language without vowel length distinctions.

You know how Spanish speakers speak French? It’d be close to that.

Answered 2017-07-06 · Upvoted by

, Linguistics PhD candidate at Edinburgh. Has lived in USA, Sweden, Italy, UK.

Why does the unmarked “or” usually imply the exclusive meaning in natural languages?

Tamara Vardo’s answer is most of the answer.

I think there’s a psychological component as well, though this is getting into speculation. It’s convenient for implicature to have xor on a scale before and, and to require the less natural notion of inclusive or to be expressed as a combination of the two, rather than allow it to be implicit.

But there is a notion underlying this, that xor is a more natural notion than inclusive or, to begin with. And that’s likely to do with humans making sense of the world through binary opposition: the notion that things are either X or Y, but not both, is very helpful if you’re trying to classify the world. The notion of things being both X and Y does not really challenge a model of the world through binary opposition: you’re just introducing a new binary opposition.

But I think the notion that things may be either X or Y, and you don’t care whether they’re both or not—which is what inclusive or means—undermines binary classification. Which is why it’s not the default.

See also: Which natural language differentiates exclusive and inclusive or?

Why do we not use morpheme analyzers for English language?

Do you mean, why is something as ludicrously unlinguistic as Snowball the state of the art of stemming in English? And why do we stem words, instead of doing detailed analysis of affixes, when we parse words in Natural Language Processing of English?

Because English lets us get away with it.

- There’s not a lot of morphology compared to other languages, and its morphophonemics is relatively clean, with some respelling rules—so stripping off suffixes is doable.

- Syntax does more work than inflection, so it’s not as critical to understand the inflections to work out what is going on in the sentence meaning.

- There’s limited and predictable amounts of inflection in English, so stemming is not that onerous. (The Snowball stemmer for English is quite a small program.)

- Our derivational morphology is only somewhat productive—so we can throw that work back on the lexicon; you couldn’t do that as readily for Turkish.

As a linguist, reading Snowball is deeply offensive. And if anyone is building a search engine for English text, and *not* adding a list of exceptions to your Snowball stemmer, you are doing your users a disservice. But English is such that it’s not as big a deal as it would be for other languages.

What is the difference between η and ᾱ in classical Greek (first declension FEM nouns)?

Dialectal.

To clarify, the question is about the nominative singular ending of first declension feminine nouns.

Some of those nouns end in a short -ă, and they’re accented accordingly on the antepenult: thálassa “sea”.

The remainder end in either a long -ā or a long -ē.

The difference in Classical Greek is a matter of dialect.

- Proto-Greek, along with Doric and Aeolic, used -ā. So “day” was hāmérā.

- Ionic regularly changed ā pretty much everywhere to ē (aː > æː > ɛː). So “day” was hēmérē.

- Attic famously was in between: it changed ā to ē, except after r, e, or i. So “day” was hēmérā.

- The rule gets violated on occasion, because it wouldn’t be Ancient Greek if there weren’t exceptions. The exception is when there used to be a digamma (w) between the r and the ē: kórwā “maiden” went to kórwē in Attic, because the ā wasn’t following an r at the time. Then the w dropped out, and the word ended up as kórē.

Things got unpredictable in the Koine, because dialects got mixed up, and because Latin loans messed things up as well by keeping their final a.

The basis of Modern Greek is Attic, but there has been some analogy at play; ē (now i) can be used after r, though still not after e or i (they’ve been merged phonetically in that context to [j]). So the adjective “second” has gone from deutérā to ˈðefteri. But “thick” has gone from pacheíā to paxˈja [paˈça].

What is the Greek word for “one’s lot in life?”

I vaguely recall a story which hangs on the following premise: there’s a Greek word which can either mean lot or some type of food (omelette?).

This one continues to have me stumped. Both the Homeric moros and the Classical moira “fate” are derived from the word for “share”, just as “lot” in English is. moira has been a homophone of myrrha “myrrh” for maybe 1500 years (first as /myra/ then as /mira/); but I’m not seeing that pun.

Of Modern synonyms, other than those in Konstantinos Konstantinides’ answer, there’s

- ɣrafto “what is written”

- riziko “what is at the root” (possibly also the etymology of risk, though I think the semantic development is different: risk < shoal at sea < boulder fallen from a cliff < cliff < (mountain root)”: What is the etymology and origin of the word “risk”?)

- pepromeno “what is fulfilled” (ancient participle, learnèd)

Nothing obvious there. The only halfway possible parallel, from this Synonyms Blog: μοίρα, is meriða. The main meaning of the word is portion (of food), and you can order a meriða of lamb at a restaurant. But the synonym list posits it’s also a synonym of fate (via the same metaphor of sharing as lot and moira.) That meaning is not given in the Triantafyllidis Dictionary, but it is one of the definitions given in Kriaras’ Dictionary of Early Modern Greek (Nathanael Bertos, 15th century: “The blasphemer has no part with God, but his portion is rather with the traitor Judas”), so it must have survived in some dialect or other.

Here’s a PhD on Bertos, if you feel like reading up on 15th century sermonising in Greek: http://ikee.lib.auth.gr/record/2…. Yes, the PhD is in Greek too.

This seems like a stretch; I’m sure that word isn’t it either. Thanks for the Google search you made me do though. Turns out Bertos’ homilies have just been published by Athanasiadou-Stephanoudaki, who wrote that PhD; I didn’t know that, and it’s always good to get more Early Modern Greek prose!

EDIT:

I think I’ve got it.

A strapatsaða is one of the names for a tomato and feta omelette; it’s also known as kaɣianas (from Turkish), and it’s equivalent to the Turkish menamen.

strapatsaða < Venetian strapazzada < strapazzare.

strapazzare: to abuse, maltreat something; to chop into little pieces.

There’s another cognate of strapazzare in Greek: strapatso “disaster, fiasco”.

It’s not the notion of “all sorts of stuff going on”, which OP recalls (and which is proverbially is associated with omelettes). But it’s the closest I’m getting.

Is there an aorist in English grammar?

I’d argue there is. Aorist means “indefinite”, and was intended to mean “indefinite (unmarked) as to aspect”, which the Greek Aorist tense was, contrasting with both the Imperfect and the Perfect tense.

Tense naming conventions, however, are dependent on different grammatical traditions. Latin did not refer to aorists, and neither did Germanic grammars or Romance grammars; “simple past” is the term usual there.

Looking at Preterite – Wikipedia, I see that the English past “sometimes (but not always) expresses perfective aspect”. That would make it not so aorist. Then again, there were plenty of Classical Greek aorists that referred to completed actions—the aorist was the default tense, and you used the perfect only to emphasise that the action was completed.

So… yes, you can argue that the simple past is an aorist; but there’s no real point in changing the terminology of English grammar to say so.

If languages are best learned from immersion, how is it possible to revitalize dead languages?

Through immersion.

Please read Daniel Ross’ answer and Jens Stengaard Larsen’s answer, which address the bulk of this.

The language you’re reviving is likely not going to be identical to the original language, as Jens points out; and that’s ok. I have a friend involved in language revival; she’s helping indigenous Australians reclaim their languages, and she’s careful to let them take the lead in the work (as you have to be). Because of both the dynamics of the situation (she’s not indigenous), and the fact that the community members are not professional linguists, she’s ended up skipping things like the ergative.

Yes. The ergative.

And that’s ok. The point after all is not to go back in a time machine and speak an identical language to that of the passed ancestors (even if that is the dream). The point is to revive something, and call it your own. And the most effective way to learn a language is still immersion, even if what you end up learning is not as historically sound.

Just as whatever got revived in the kibbutzim of Palestine was not a carbon copy of the Hebrew of King David: Hebrew had remained in use as a scholarly language, but there was plenty of Yiddish that got added to the mix, to get it speakable. The point was that the real revival of Hebrew happened in the kibbutzim, and not in the household of Eliezer Ben-Yehuda. There was immersion in both places; the immersion in the kibbutzim was less meticulous than what happened to Itamar Ben-Avi—but also more humane, and more scalable.

At least the kids growing up in the kibbutzim were allowed to have friends who didn’t speak Hebrew.

Population of Jerusalem speaking Hebrew when Itamar was a kid: 1.

Why was Heracles named after Hera, when his real mother was Alcmene?

The in-universe explanation (to treat Greek mythology like fantasy fiction, and that’s not that absurd really) is

He was renamed Heracles [“glory of Hera”] in an unsuccessful attempt to mollify Hera. (Heracles – Wikipedia)

Stepping behind the curtain, in his monograph on Greek religion (p. 322), Walter Burkert says the name might be a coincidence; but he thinks it likelier that Heracles being subject to Eurysthenes and his protector goddess Hera, and the multiple instances where Heracles cross-dressed, point to a hero whose very point was that he could fall from being the son of Zeus to being disempowered (oppressed by a female goddess, cross-dressing like a woman).

Why don’t most Modern English speakers rhyme “thou” with “you”?

From OED, the dialectal survivals like Yorkshire thaa reflect unstressed variants of thou (which were short); thou is a long vowel that has gone through the Great English Vowel Shift—just as house has an /aʊ/ vowel, and is still pronounced huːs in Scots.

The irregularity is you, and apparently the yow pronunciation was around in the 17th century and survives in dialect. OED has a somewhat convoluted account, but the bit of it I find convincing is ēow > you patterning with new, as a /iuː/ instance exempt from the Vowel Shift:

In early Middle English the initial palatal absorbed the first element of the diphthong /iu/ (the regular reflex of Old English ēo plus w ), resulting, after the shift of stress from a falling to a rising diphthong, in /juː/; a stage already reached (in some speech) by the early 13th cent. (compare the form ȝuw in the Ormulum). Middle English long ū thus produced was subject to regular diphthongization to /aʊ/ by the operation of the Great Vowel Shift, as is attested by some 16th- and 17th-cent. orthoepists, who also provide evidence that by the second half of the 17th cent. this pronunciation had come to be regarded as a vulgarism; it survives in a number of modern regional English varieties. The modern standard pronunciation derives partly from a Middle English unstressed variant with short ŭ , subsequently restressed and lengthened, and partly from a form which preserved the falling diphthong /iu/ and subsequently shared the development of other words with this sound (e.g. new adj., true adj.) in which the shift of stress to /juː/did not take place until later; see further E. J. Dobson Eng. Pronunc. 1500–1700 (ed. 2, 1968) II. §§4, 178.

(The unstressed variant of you with short ŭ would be pronounced yuh; it is of course the form usually spelled ya.)